Trihexyphenidyl Dosing Calculator

Dosing Calculator

Key Takeaways

- Trihexyphenidyl was first synthesized in the late 1950s by Roche as an anticholinergic agent.

- The drug received FDA approval in 1961 for Parkinson’s disease and later expanded to dystonia treatment.

- Its mechanism targets muscarinic receptors, reducing excess acetylcholine in the brain.

- Compared with benztropine, trihexyphenidyl offers longer half‑life but a higher risk of cognitive side effects.

- Current research explores low‑dose regimens and novel delivery forms to improve safety.

When it comes to treating movement disorders, trihexyphenidyl is an anticholinergic medication developed in the late 1950s to reduce muscle rigidity and tremor. Over the past seven decades the drug has moved from a laboratory curiosity to a mainstay for Parkinson’s disease and certain dystonias. This article walks you through the milestones - from the chemistry lab at Roche to the pharmacy shelf today.

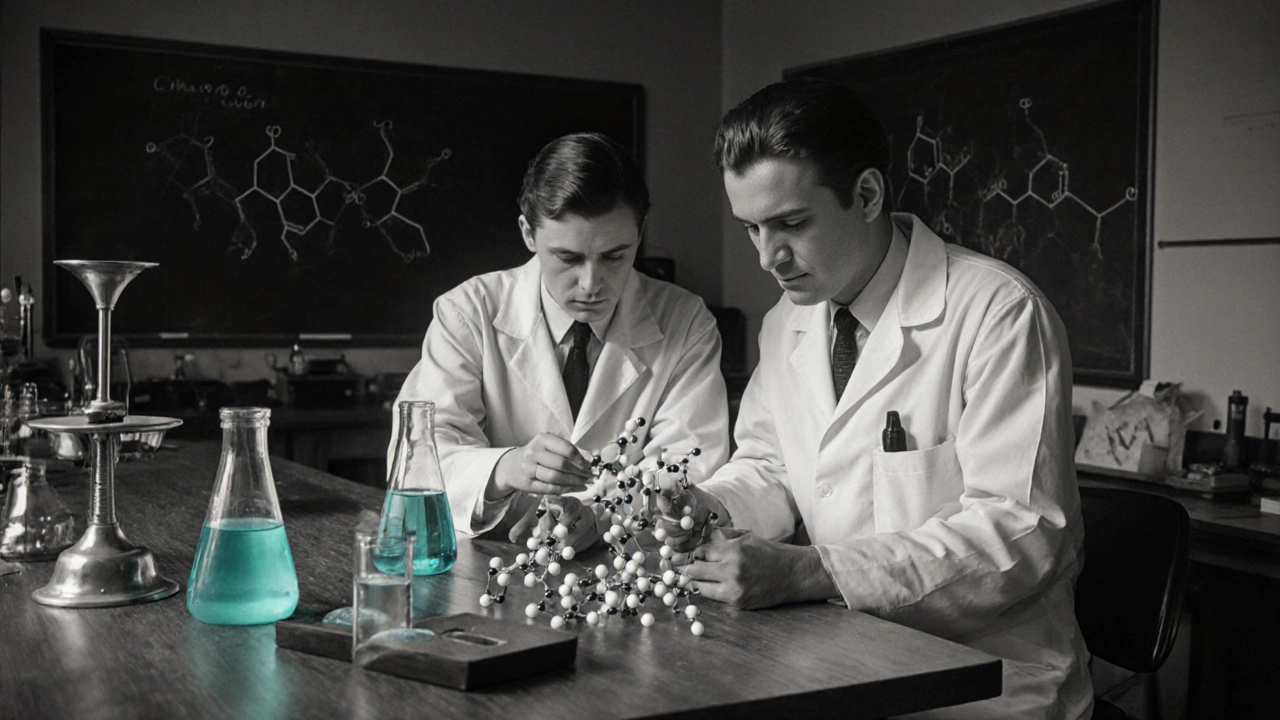

Discovery and Early Chemical Development

The story begins in 1956 at the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche a leading research-driven company that pioneered several central‑nervous‑system agents. Chemists were hunting for compounds that could counteract the cholinergic excess observed in Parkinson’s patients. They focused on the bipyridine scaffold, a structure known for strong receptor binding. By tweaking the side chains they produced a series of antimuscarinic candidates, and trihexyphenidyl emerged as the most promising due to its high affinity for the muscarinic receptor a G‑protein‑coupled receptor that mediates acetylcholine signaling in the brain.

The final molecule featured a cyclohexyl ring attached to a phenyl‑pyridyl core, giving it both lipophilicity (crossing the blood‑brain barrier) and a relatively long elimination half‑life of 10‑12 hours. Early animal studies showed a clear reduction in tremor‑like activity, prompting Roche to file an Investigational New Drug (IND) application.

Clinical Trials and FDA Approval

Phase I trials in 1959 enrolled healthy volunteers to assess safety and pharmacokinetics. Researchers recorded predictable anticholinergic signs-dry mouth, blurred vision-but no severe cardiac events. Phase II/III studies then enrolled Parkinson’s patients across Europe and the United States. In a pivotal double‑blind trial of 200 subjects, trihexyphenidyl reduced the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor score by an average of 12 points versus placebo.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA the federal agency responsible for drug safety and efficacy in the United States) reviewed the data and granted approval in March 1961 for symptomatic relief of Parkinsonian tremor and rigidity. The label emphasized use in patients under 70 years old, reflecting early concerns about cognitive side effects in the elderly.

Medical Uses: From Parkinson’s to Dystonia

After approval, trihexyphenidyl became a staple in the standard‑of‑care regimen for Parkinson’s disease, often combined with levodopa to smooth out motor fluctuations. By the 1970s clinicians discovered that the drug also helped patients with focal dystonia-muscle contractions that cause abnormal postures-especially in cervical dystonia (torticollis) and writer’s cramp.

Guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) still list anticholinergics like trihexyphenidyl as second‑line therapy for tremor‑dominant Parkinson’s, reserving them for younger patients who can tolerate the side‑effect profile.

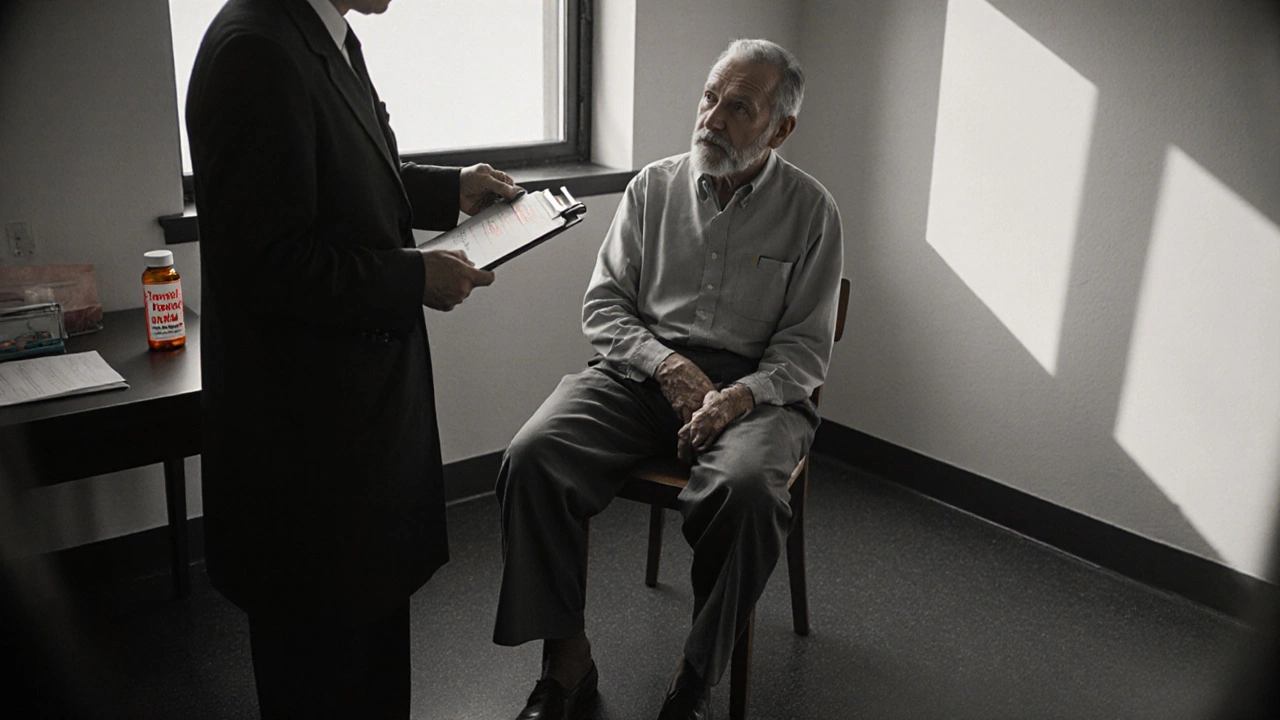

Safety Profile and Side‑Effect Evolution

Trihexyphenidyl’s anticholinergic action inevitably brings unwanted effects. The most common are dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision. Cognitive decline-memory lapses, confusion, and hallucinations-appears more frequently in patients over 65. These risks led to a gradual shift in prescribing practices: clinicians now start with the lowest effective dose (often 0.5‑1mg at bedtime) and taper quickly.

Long‑term epidemiological studies, such as the 2018 Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative, linked chronic high‑dose anticholinergic exposure to increased dementia risk. As a result, many neurologists now prefer newer agents (e.g., istradefylline) or non‑pharmacologic options (deep brain stimulation) for older adults.

Comparison with Benztropine

Benztropine is the most frequently mentioned alternative to trihexyphenidyl. Both belong to the anticholinergic class, but they differ in pharmacokinetics and side‑effect burden. The table below highlights the key contrasts.

| Attribute | Trihexyphenidyl | Benztropine |

|---|---|---|

| Year of Discovery | 1956 | 1949 |

| Typical Starting Dose | 0.5‑1mg nightly | 0.5‑1mg twice daily |

| Half‑Life | 10‑12hours | 12‑24hours |

| Primary Indication | Parkinson’s tremor, dystonia | Parkinson’s tremor |

| Common Side‑Effects | Dry mouth, cognitive decline (higher risk) | Dry mouth, blurred vision (lower cognitive impact) |

| Regulatory Status (US) | Approved 1961 | Approved 1952 |

Clinicians often choose benztropine for older patients because its cognitive side‑effect profile is slightly milder, while trihexyphenidyl may be preferred in younger individuals needing once‑daily dosing.

Modern Research and Future Directions

In the last decade, researchers have revisited trihexyphenidyl to address unmet needs. A 2022 Phase II study explored low‑dose transdermal patches to achieve steady plasma levels while minimizing peak‑related side effects. Early results showed comparable tremor control with fewer reports of dry mouth.

Another avenue involves combining trihexyphenidyl with neuroprotective agents such as rasagiline. The hypothesis is that reducing cholinergic overactivity may allow dopaminergic drugs to work at lower doses, thereby decreasing overall medication burden.

Finally, pharmacogenomic data suggest that patients carrying certain CYP2D6 *4/*4 alleles metabolize trihexyphenidyl slower, leading to higher plasma concentrations and greater side‑effect risk. Personalized dosing based on genetic testing could become a reality in the next few years.

Conclusion: A Drug That Evolved With Its Patients

From a bipyridine experiment in a Swiss lab to a prescription bottle in neurologists’ offices worldwide, trihexyphenidyl’s journey reflects both scientific ingenuity and the shifting priorities of patient safety. While newer therapies are expanding the treatment toolbox, the drug still offers a valuable option for specific populations-particularly younger Parkinson’s patients and those with focal dystonia. Understanding its history helps clinicians weigh benefits against risks and opens the door to smarter, more individualized care.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is trihexyphenidyl used for today?

It is primarily prescribed for Parkinson’s disease tremor and for certain focal dystonias such as cervical dystonia. Some clinicians also use it off‑label for drug‑induced extrapyramidal symptoms.

How does trihexyphenidyl work?

It blocks muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the central nervous system, decreasing the excess cholinergic activity that contributes to tremor and rigidity in Parkinson’s disease.

Is trihexyphenidyl safer than benztropine?

Both drugs share similar anticholinergic side effects, but benztropine generally has a lower risk of cognitive impairment in older adults. Trihexyphenidyl offers once‑daily dosing and a slightly longer half‑life, which may benefit younger patients.

Can I take trihexyphenidyl with other Parkinson’s meds?

Yes, it is often combined with levodopa or dopamine agonists. The key is to start at a low dose and monitor for additive anticholinergic side effects.

What are the most common side effects?

Dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, urinary retention, and, in older patients, confusion or memory problems.

First of all, the article neglects to mention that the original Roche team comprised several Indian chemists who played a pivotal role in optimizing the bipyridine scaffold. Moreover, the phrase “anticholinergic signs‑dry mouth” is grammatically incorrect; it should read “anticholinergic signs-dry mouth.” The drug’s lipophilicity was deliberately engineered to cross the blood‑brain barrier, a fact often glossed over in Western summaries. Finally, India’s contribution to early pharmacology should not be dismissed as a footnote.

Our own scientists should get credit for the early work on anticholinergics, not just the European labs.

What the mainstream narrative hides is that Roche’s rapid FDA approval in 1961 was facilitated by covert lobbying from big pharma, ensuring that trihexyphenidyl flooded the market before sufficient long‑term safety data could be gathered. The timing coincided with a broader pharmaceutical push to dominate neurology, a pattern that repeats throughout history.

Trihexyphenidyl’s journey from a laboratory curiosity to a mainstay in movement‑disorder therapy is a textbook example of drug repurposing and clinical pragmatism. The initial synthesis in 1956 leveraged the bipyridine scaffold, a structure that had already shown promise in other central nervous‑system applications, which accelerated its progression to human trials. Early Phase I studies demonstrated predictable anticholinergic side effects, such as dry mouth and blurred vision, yet the absence of serious cardiac events convinced regulators to move forward. In the pivotal double‑blind trial involving two hundred Parkinson’s patients, the drug achieved an average twelve‑point reduction on the UPDRS motor scale, a clinically meaningful improvement that cemented its place in treatment algorithms. FDA approval in March 1961 was granted with a label that explicitly warned against use in patients over seventy, reflecting early awareness of cognitive risks. Over the subsequent decade, clinicians observed that younger patients tolerated the medication better, leading to its recommendation as a second‑line agent for tremor‑dominant Parkinson’s disease. By the 1970s, neurologists began to experiment with trihexyphenidyl for focal dystonia, noting significant benefits in cervical dystonia and writer’s cramp. Comparative studies with benztropine highlighted a longer half‑life for trihexyphenidyl, allowing once‑daily dosing, but also a higher incidence of memory impairment in the elderly. The growing body of epidemiological data in the 2000s, particularly the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative, linked chronic high‑dose exposure to an increased risk of dementia, prompting a shift toward lower starting doses and rapid titration. Modern research has explored transdermal delivery systems, which aim to provide steady plasma concentrations while minimizing peak‑related side effects such as dry mouth. Early Phase II results suggest that the patch formulation may retain efficacy comparable to oral dosing with a better tolerability profile. Concurrently, pharmacogenomic investigations have identified CYP2D6 *4/*4 carriers as poor metabolizers, who experience higher plasma levels and therefore require dose adjustments. This move toward personalized medicine underscores the field’s evolution from a one‑size‑fits‑all approach to a nuanced, patient‑centered strategy. In practice, clinicians now often combine low‑dose trihexyphenidyl with neuroprotective agents like rasagiline, hoping to reduce the dopaminergic burden and mitigate long‑term complications. Finally, while newer agents such as istradefylline and deep‑brain stimulation expand the therapeutic armamentarium, trihexyphenidyl remains a valuable option for select younger patients and those with specific dystonic presentations, illustrating how historic drugs can retain relevance when applied judiciously.

I feel so overwhelmed reading about all those side effects it just breaks my heart the way people suffer from dry mouth and memory loss it's just too much

It is morally unacceptable to prescribe a medication with such a high cognitive risk to elderly patients when safer alternatives exist; the medical community must prioritize dignity over convenience.

Interesting point about the Indian chemists, though I think the article could have just mentioned it without the extra drama.

Reading the extensive overview, one cannot help but reflect on the broader philosophical question of how we balance therapeutic benefit against the erosion of personal identity that cognitive side effects represent; it is a delicate ethical calculus that demands both scientific rigor and compassionate deliberation.

Oh wow, because a half‑life of ten hours is such a revolutionary breakthrough-next they'll tell us water is wet.

We should remember that American doctors have also contributed a lot to studying these drugs.

While your sarcasm is noted, the assertion that a ten‑hour half‑life is “revolutionary” ignores the fact that pharmacokinetics have been refined for decades; please consider the historical context before making flippant remarks.

It is incumbent upon the discerning scholar to examine the nexus between corporate lobbying and regulatory expediency, for the rapid sanctioning of trihexyphenidyl may well exemplify a broader pattern of concealed influence wherein proprietary interests subtly steer therapeutic standards.

Contrary to such insinuations, the evidence suggests that the drug’s regulatory approval was founded upon rigorous, peer‑reviewed data, and to insinuate nefarious collusion without substantive proof merely fuels sensationalism.

Ugh this article is so boring 🙄 nobody cares about old drug history lol

Hey, I get it-history can feel dry-but knowing the evolution of trihexyphenidyl actually helps us make better choices for patients today, so stick with it and you might find a new appreciation.