When a patient picks up a generic pill, they might not think about what’s inside beyond the active ingredient. But for many people around the world, the color, shape, size, or even the gelatin in the capsule matters more than they realize. In Auckland, where over 40% of residents identify as non-European, pharmacists are learning the hard way that a one-size-fits-all approach to generics doesn’t work. A Muslim patient refusing a capsule because it contains pork-derived gelatin. A Vietnamese elder refusing a white pill because, in their culture, white means mourning. A Hispanic patient convinced the generic version of their blood pressure medicine is weaker because it looks different from the branded one they used back home. These aren’t rare cases. They’re daily realities in multicultural healthcare.

Why Generics Look Different - And Why It Matters

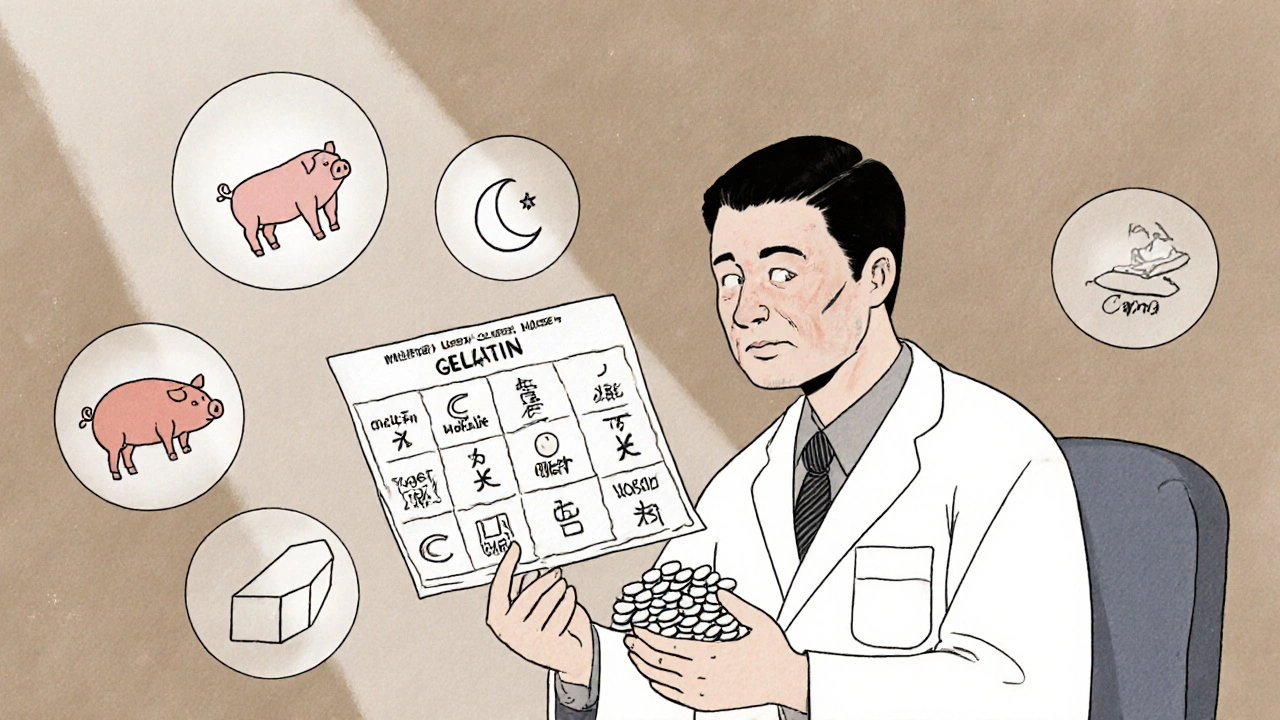

Generic drugs contain the same active ingredient as their brand-name counterparts. That’s the law. But everything else - the fillers, dyes, coatings, and capsule shells - can be completely different. These are called excipients. And while they don’t treat your condition, they can stop you from taking your medicine at all. In Europe, 70% of all pills sold are generics. In the U.S., it’s over 90%. But here’s the problem: most of these generics were designed for a single cultural context - usually white, English-speaking, Western patients. The result? A medication that works chemically but fails socially. A 2023 study in the U.S. found that 28% of African American patients believed generics were less effective than brand-name drugs. Only 15% of non-Hispanic White patients felt the same. Why? Because in some cultures, the appearance of a pill is tied to trust. A bright blue pill might mean “strong medicine” to one person. To another, it might mean “poison.”Religious and Cultural Restrictions in Medication Ingredients

Some ingredients in medications aren’t just harmless fillers - they’re sacred or forbidden. - Halal requirements: For many Muslims, gelatin from pigs is strictly prohibited. Many capsules, especially for cholesterol or diabetes meds, use pork gelatin. A pharmacist in Wellington told a researcher they spent two hours calling manufacturers just to find a vegetarian alternative for one patient. - Kosher standards: Jewish patients may avoid medications containing animal byproducts unless certified kosher. This includes certain liquid suspensions and tablets with animal-derived lubricants. - Vegetarian and vegan beliefs: Some patients refuse all animal products. That includes lactose (often used as a filler) or gelatin. Even if the active drug is plant-based, the capsule might not be. A 2023 survey of urban pharmacies found that 63% of pharmacists received requests about excipients at least once a week. Yet only 37% of generic medication labels in the U.S. list these ingredients clearly. In the EU, that number is 68%. That gap isn’t just bureaucratic - it’s dangerous.Color, Shape, and the Psychology of Medicine

Colors aren’t just for branding. They carry meaning. - In many East Asian cultures, red pills are seen as powerful and effective. Yellow or green might be associated with sickness or weakness. - In parts of Latin America, white pills are often linked to death or funerals. Patients may refuse them outright. - In India, large, round pills are associated with traditional Ayurvedic medicine. Small, oblong pills may be seen as “Western” or “artificial,” even if they’re identical in dosage. One patient in Christchurch refused her generic antidepressant because it was a small white oval - the branded version was a large blue round tablet. She said, “If it looks like a different medicine, how do I know it works?” She stopped taking it. Her depression returned. These aren’t irrational fears. They’re rooted in real experiences. Many patients come from countries where counterfeit drugs are common. In those places, appearance is the only way to tell if a pill is real. When they land in a new country and their medicine suddenly looks different, it triggers deep suspicion.

The Role of Language and Communication

A patient might understand their condition perfectly. But if the instructions on the bottle are in English, and they speak only Mandarin or Samoan, they’re at risk. Generic medications often come with minimal labeling. No pictures. No translations. Just small print in one language. Pharmacists in Auckland report that patients frequently misread dosages - taking twice as much because they thought “once daily” meant “every 12 hours.” Or skipping doses because they didn’t understand “take with food.” Simple fixes help: pictograms, multilingual inserts, video instructions in community languages. But most pharmacies don’t have the resources. Training staff in cultural communication isn’t mandatory. It’s optional. And too often, it’s ignored.What’s Being Done - And What’s Not

Some companies are starting to catch up. Teva Pharmaceutical launched a “Cultural Formulation Initiative” in 2023 to document all excipients across 15 major drug classes. Sandoz is building a global framework for culturally appropriate generics. These are steps in the right direction. But change is slow. Only 22% of community pharmacies in the U.S. have formal training on cultural considerations for generics. In New Zealand, it’s likely lower. Most pharmacists learn on the job - by trial and error. The real barrier isn’t lack of knowledge. It’s lack of systems. There’s no centralized database of which generics contain pork gelatin, which are vegan, which are kosher-certified. Pharmacists have to call manufacturers. Search through old paperwork. Guess. That takes time - time most pharmacies don’t have.

What Patients and Providers Can Do Today

You don’t need a corporate policy to make a difference. For patients: - Ask: “Does this pill have gelatin? Is it made from animals?” - Ask: “Is there another version that looks more like the one I used before?” - Ask: “Can I get this in liquid form?” (Many liquids avoid gelatin capsules.) - Don’t be afraid to say no. Your beliefs matter. For pharmacists and clinicians: - Always ask about cultural or religious concerns when dispensing generics. Don’t assume they don’t matter. - Keep a local list of pharmacies or suppliers that stock halal, kosher, or vegetarian generics. - Use visual aids - pictures of pill shapes and colors - when explaining substitutions. - Advocate for better labeling. Push manufacturers to include excipient details on packaging.The Bigger Picture: Equity in Medicine

This isn’t just about pills. It’s about trust. Historically, marginalized communities have been excluded from clinical trials, underdiagnosed, and overmedicated. When a patient is handed a generic pill that looks wrong, smells wrong, or feels wrong - and no one listens - it reinforces the idea that their needs don’t count. The solution isn’t to stop using generics. They save billions and make life-saving drugs affordable. The solution is to make them inclusive. By 2027, 65% of major generic manufacturers plan to include cultural considerations in their product design. That’s progress. But it shouldn’t take five years for a Muslim child to get their asthma inhaler without pork gelatin. Medicine isn’t just chemistry. It’s culture. And if we want patients to take their meds - really take them - we have to meet them where they are. Not just in their language. Not just in their symptoms. But in their beliefs, their fears, their traditions.Frequently Asked Questions

Why do generic pills look different from brand-name ones?

Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient as the brand-name version, but they can use different fillers, dyes, and capsule materials. These differences are legal and safe, but they can change the pill’s color, shape, or size. For some patients, these visual changes trigger doubts about effectiveness or raise cultural or religious concerns.

Are generic medications less effective than brand-name drugs?

No. By law, generics must meet the same standards for safety, strength, and absorption as brand-name drugs. Studies show they work just as well. But perception matters. In some cultures, a pill’s appearance is tied to trust. If a patient believes a different-looking pill is weaker, they may stop taking it - which makes the medicine seem ineffective, even if it’s not.

What are excipients, and why do they matter in multicultural care?

Excipients are inactive ingredients like gelatin, lactose, dyes, or preservatives. They help the pill hold its shape or be absorbed. But for some people, these ingredients conflict with religious rules (like pork gelatin for Muslims) or personal beliefs (like avoiding animal products for vegans). If a patient finds out their medicine contains something forbidden, they may refuse it - even if it’s medically necessary.

Can I ask my pharmacist for a generic with different ingredients?

Yes. You have the right to ask for alternatives. If your current generic contains gelatin, lactose, or a dye you avoid, ask your pharmacist if another brand or formulation is available. Many pharmacies keep lists of halal, kosher, or vegetarian-friendly generics. It might take a few calls, but it’s possible.

Why don’t generic labels list all ingredients clearly?

In the U.S., manufacturers aren’t required to list excipients in detail on the label. Only 37% of generic packages include full ingredient lists. In the EU, it’s 68%. This lack of transparency makes it hard for patients and pharmacists to make informed choices. Advocacy and regulatory pressure are needed to change this.

For years, I’ve worked in community health and seen this firsthand. A patient once refused her insulin because the capsule was yellow - she said it reminded her of the jaundiced babies in her village. We switched to a clear liquid form. She’s been stable for two years now. It’s not about superstition. It’s about trust. And trust is built on respect, not just chemistry.

Look this is basic stuff. If you can't tell the difference between a generic and a brand name pill you shouldn't be taking meds at all. People need to stop being dramatic. It's the same active ingredient. End of story. If you're too sensitive to pill color you're probably the reason we have an opioid crisis.

OMG YES!!! In India, we have this problem ALL THE TIME!!! My aunty refused her BP pills because they were small and white - she said it looked like ‘poison powder’ from TV dramas 😭 We had to get her the big blue ones from a private pharmacy - cost 3x more but she took it! 🙏💊 #CultureMatters

Medicine isn’t just science. It’s human. And humans carry stories in their bones. If a pill looks wrong to someone, it’s not irrational - it’s rooted in survival. We treat the body, but we forget the soul that carries it.

As a Filipino-American, I’ve seen my mom cry because her generic antidepressants were pink - in our culture, pink = bad luck for mental health. We found a white one. She cried again - this time from relief. This isn’t ‘cultural sensitivity’ - it’s basic dignity. 🙏

This is systemic negligence dressed up as ‘cost-saving.’ We’ve built a healthcare system that prioritizes efficiency over equity. And then we wonder why adherence rates are abysmal in marginalized communities. It’s not patient ignorance - it’s institutional indifference.

Let me tell you something - this whole ‘cultural pill thing’ is just woke nonsense wrapped in a lab coat. People in the UK take generics without a second thought. If you can’t handle a different color pill, maybe you’re not ready for modern medicine. It’s not 1920 anymore. We don’t need to coddle every superstition just because someone moved from a village to a city. It’s just a pill.

They’re not just hiding gelatin in capsules… they’re hiding the truth. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know what’s in those little pills - because if you knew, you’d refuse. Pork gelatin? Lactose? Dyes linked to ADHD? And they don’t even label it properly? That’s not negligence - that’s deliberate obfuscation. And the FDA? They’re asleep at the wheel. Wake up people - this isn’t about culture, it’s about control. They want you docile. And a white pill? That’s the perfect tool.

Isn’t it fascinating how we’ve reduced the sacred act of healing to a standardized commodity? We’ve replaced ritual with regulation, and now we’re surprised when the soul rebels against the system. The pill is a symbol - and symbols carry more weight than molecules. To dismiss this as ‘irrational’ is to misunderstand the very nature of human meaning.

Did you know that over 80% of generic capsules in the U.S. use porcine-derived gelatin? That’s not an accident - it’s a supply chain optimization. The cost of bovine gelatin is 3x higher. So they go with the cheapest. And then they wonder why Muslim patients drop out of treatment. It’s not ignorance - it’s economic violence. We need a federal excipient registry. Now. Not in 2027. Now.

It is imperative that healthcare institutions implement standardized cultural competency protocols for the dispensing of generic pharmaceuticals. This includes mandatory training, multilingual labeling, and transparent excipient disclosure. Failure to do so constitutes a breach of the ethical obligation to provide equitable care. The current state of affairs is untenable and demands immediate systemic intervention.

Why are we letting foreigners dictate how our medicine looks? We got the best science in the world. If you can't handle a white pill, go back to your country. This isn't a multicultural art project - it's medicine. And medicine doesn't care about your beliefs. It cares about results.