OpenFDA Drug Side Effect Search Tool

Simulated Drug Side Effect Search

Try searching for side effect reports using the OpenFDA API. This tool simulates results based on the article's examples. Remember: real data may differ.

Important Notes

- Note Results shown are simulated based on the article's examples, not actual API data

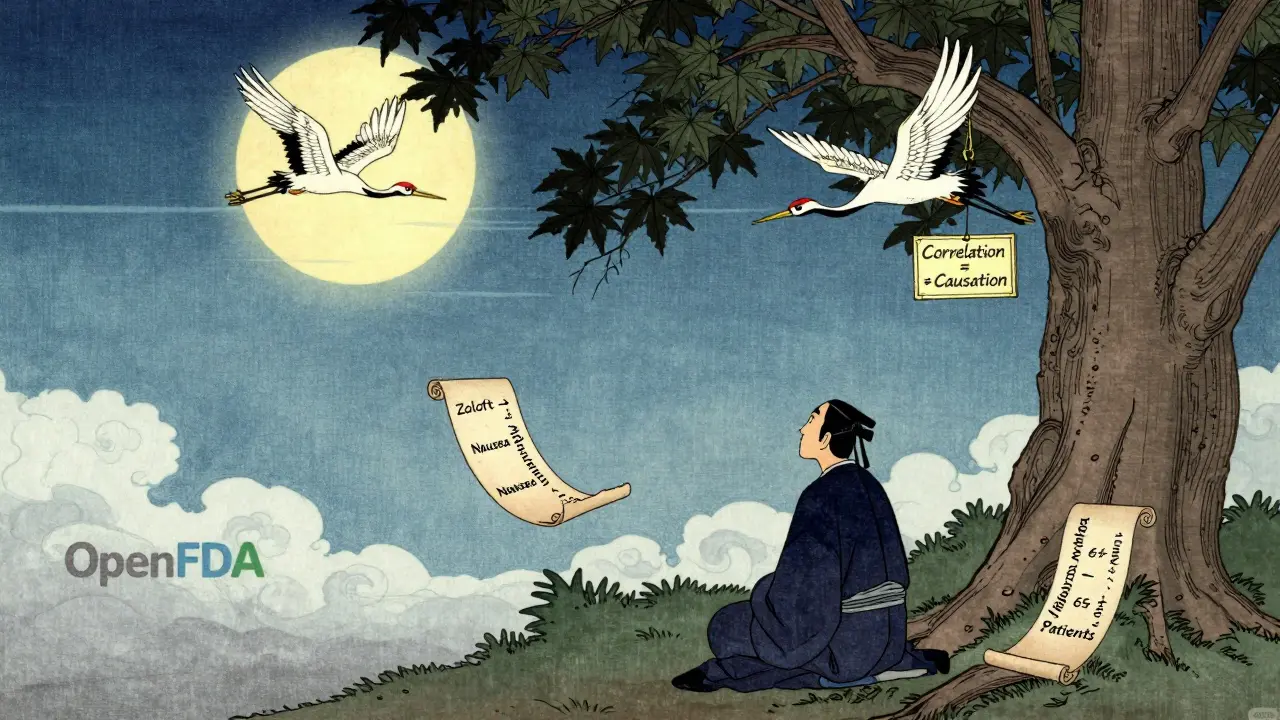

- Caution Correlation ≠ Causation: Side effect reports don't prove drugs cause adverse events

- Data Limit Real data may contain underreported side effects (less than 10% of actual incidents)

- Privacy Patient identities are always removed for privacy protection

What OpenFDA and FAERS Really Are

OpenFDA is a free, public API from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that gives developers direct access to structured drug safety data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). It was launched in 2014 to break down the barriers that once made it nearly impossible for researchers, developers, and even concerned patients to get clean, usable data on drug side effects.

Before OpenFDA, getting adverse event reports meant downloading massive XML files from the FDA website, then spending days cleaning and sorting them. The data was buried under layers of bureaucracy and outdated formats. Now, with OpenFDA, you can ask for side effect reports for a specific drug - like ibuprofen or metformin - and get a clean JSON response in seconds.

The FAERS database holds over 14 million reports of adverse events linked to drugs, medical devices, and dietary supplements. These reports come from doctors, pharmacists, patients, and drug manufacturers. OpenFDA doesn’t collect new data - it just makes the existing FAERS data easier to use. Think of it like a library that used to require you to dig through microfiche reels, and now has a searchable online catalog.

How the API Works - No PhD Required

OpenFDA uses Elasticsearch under the hood, which means you need to write queries in a specific format. But you don’t need to be a data scientist to use it. Here’s how a basic query looks:

https://api.fda.gov/drug/event.json?search=openfda.generic_name:"ibuprofen"&limit=100

This request pulls up to 100 reports where ibuprofen was listed as the suspected drug. The response includes:

- Drug name (generic and brand)

- Adverse event term (coded in MedDRA - a standardized medical language)

- Patient age and gender

- Outcome (e.g., hospitalization, death, recovery)

- Report date and source

You can filter by more than just drug names. Try searching for events linked to a specific manufacturer, route of administration (like "oral" or "intravenous"), or even the patient’s age range. For example:

https://api.fda.gov/drug/event.json?search=patient.patientage:65+AND+openfda.generic_name:"metformin"&limit=50

This finds reports from patients aged 65 or older taking metformin. The API lets you combine filters using + for AND and | for OR. It’s like Google search, but for drug safety.

API Keys and Rate Limits - Don’t Get Blocked

Anyone can use OpenFDA without an API key, but you’re capped at 1,000 requests per day. That’s enough for casual research, but if you’re running automated scripts or analyzing large datasets, you’ll hit that limit fast.

Registering for a free API key at open.fda.gov/apis/authentication/ bumps your limit to 120,000 requests per day and 240 per minute. That’s more than enough for academic research or small-scale applications.

Here’s what happens if you go over the limit: you get a 429 error - "Too Many Requests." The system doesn’t ban you. It just pauses you for a minute. If you’re building something that needs to run overnight, build in delays. A 1-second pause between requests keeps you safe and polite.

Some developers use Python or R packages to handle this automatically. The R package openFDA lets you set your key with set_api_key() and handles pagination and throttling behind the scenes. If you skip this step, you’ll see an error: "No openFDA API key was found by keyring::key_get()." It’s not a bug - it’s a reminder to register.

What You Can - and Can’t - Do With This Data

OpenFDA is powerful, but it’s not magic. Here’s what you need to understand before drawing conclusions:

- Correlation ≠ Causation - Just because someone took a drug and then had a heart attack doesn’t mean the drug caused it. The report might be from a 78-year-old with diabetes, high blood pressure, and a history of heart disease. The drug might have nothing to do with it.

- Data is delayed - Reports take time to get into the system. You’re looking at data that’s up to three months old. Real-time monitoring? Not happening.

- No patient identities - For privacy, names, addresses, and medical record numbers are stripped out. You can’t track individuals. That’s good for privacy, bad for longitudinal studies.

- Underreporting is massive - Studies estimate less than 10% of all adverse events are ever reported. Most people don’t know they can report side effects. Most doctors don’t bother.

OpenFDA won’t tell you if a drug is "dangerous." It tells you what people have reported. That’s a starting point - not a verdict.

Real-World Use Cases - Who’s Actually Using This?

Academic researchers are the biggest users. In 2022 alone, over 350 peer-reviewed studies cited OpenFDA data. One study used it to detect a spike in liver injuries linked to a popular herbal supplement. Another tracked how often older adults were prescribed drugs that could worsen dementia.

Nonprofits and patient advocates use it too. MedWatcher, a free app for consumers, pulls OpenFDA data to show side effect trends for medications you’re taking. If you’re on Zoloft and wonder how common nausea is, it shows you real reports - not just the clinical trial numbers.

Even journalists have used it. In 2021, a team at ProPublica used OpenFDA to expose how certain painkillers were being prescribed to elderly patients despite known risks. Their report led to congressional hearings.

These aren’t theoretical uses. This data is changing how people understand drug safety.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Most people who try OpenFDA for the first time get stuck on one of these:

- Using brand names instead of generic names - Search for "ibuprofen," not "Advil." The API uses generic drug names from the FDA’s official list.

- Forgetting to URL-encode special characters - If your drug name has a slash or ampersand, the query breaks. Use tools like

encodeURIComponent()in JavaScript orurllib.parse.quote()in Python. - Assuming the data is complete - If you don’t see a side effect listed, it doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen. It might just be underreported.

- Not using pagination - You can only get 1,000 results per call. To get more, use the "skip" parameter. Example:

?search=...&limit=1000&skip=1000gets you results 1001-2000. - Ignoring MedDRA terms - "Heart attack" is coded as "Myocardial infarction." You need to know the official term. The FDA provides a MedDRA browser to look these up.

Start small. Test one drug. One side effect. One age group. Then expand.

Alternatives to OpenFDA - When You Need More

OpenFDA is free, but it’s basic. If you’re a pharmaceutical company or a hospital system needing advanced signal detection, you’ll look elsewhere.

Commercial tools like ARTEMIS and Oracle Argus cost tens of thousands of dollars a year. They do things OpenFDA can’t:

- Automatically flag unusual patterns across millions of reports

- Link reports to electronic health records

- Filter by lab results or genetic data

- Integrate with internal safety databases

But for most people - students, journalists, public health workers, curious patients - OpenFDA is more than enough. It’s the only free, official source for this kind of data. No other platform gives you this level of transparency.

Where to Go Next

If you want to dig deeper, here’s what to do:

- Visit open.fda.gov - Play with the search interface. It’s interactive and shows you the exact URL behind each search.

- Check the GitHub repo - github.com/FDA/openfda - for code examples in Python, R, and Node.js.

- Download the full FAERS data files - if you want to run your own analysis offline, the FDA still offers bulk downloads.

- Learn MedDRA - Go to meddra.org and search for common terms like "dizziness," "rash," or "nausea" to find their official codes.

There’s no certification needed. No license. No fee. Just curiosity and a little patience.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is OpenFDA data real-time?

No. OpenFDA data is updated quarterly, with a delay of up to three months. The FDA needs time to process, clean, and de-identify reports before they’re made available. You won’t see new side effect reports immediately after they’re submitted.

Can I use OpenFDA to decide whether to take a medication?

Absolutely not. The FDA clearly warns: "Do not rely on openFDA to make decisions regarding medical care." Side effect reports are incomplete, unverified, and lack context. Always talk to your doctor or pharmacist before making any changes to your medication.

Do I need to be a programmer to use OpenFDA?

No. You can use the search interface on open.fda.gov without writing any code. But if you want to analyze data at scale - like comparing side effects across 10 drugs - you’ll need basic programming skills. Python or R are the most common tools.

Why are some side effects missing from the reports?

Many reasons. Patients don’t report minor side effects. Doctors don’t always document them. Some reports are vague - "feeling unwell" isn’t useful. And because reporting is voluntary, the system relies on people caring enough to submit. This means the data is biased toward serious or unusual events.

Can I get data for medical devices or foods too?

Yes. OpenFDA has endpoints for medical devices, food safety incidents, and tobacco products. The drug endpoint is the most complete, but you can search for device malfunctions or foodborne illness reports using similar syntax. Just change the endpoint from "drug/event" to "device/event" or "food/event".

this is legit game changing for us in India where drug safety info is a black box. just tried querying for metformin and got 500+ reports in 2 seconds. no more guessing if that weird rash is from the med or monsoon humidity 😅

OpenFDA is the closest thing we have to a public health truth serum. people think it's just data but it's actually accountability in JSON form. the fact that a 16-year-old with a Raspberry Pi can uncover a pattern that Big Pharma tried to bury? that's democracy working. i'm not just impressed i'm emotional.

lol they said 'no PhD required' but you need to be a wizard to decode MedDRA. why can't they just say 'dizziness' instead of 'vertigo'? and why does every report have 17 synonyms for 'nausea'? this feels like the FDA hired a thesaurus salesman as their data architect 🤡

Let me just say this: the entire premise of OpenFDA is a dangerous illusion of transparency. You're not accessing raw data-you're accessing a sanitized, heavily curated, statistically compromised dataset that has been filtered through bureaucratic inertia and regulatory theater. The underreporting rates alone invalidate any meaningful inference. This is not science. It's performative data theater for the digital age.

I love that you mentioned MedDRA. But seriously, why isn't there a simple lookup tool built into the API? I spent 45 minutes Googling 'dizziness meddra code' and found three different versions. This is like giving someone a library and then hiding all the card catalogues. 🤦♀️

they're not just underreporting side effects... they're hiding them. why do you think the FDA delays data by 3 months? it's not 'processing time'-it's cover-up time. Big Pharma pays them. I've seen the patterns. The same drugs keep popping up in reports, then vanish from the public feed for 90 days. Coincidence? I don't think so. 🕵️♂️

so you're telling me a guy in Ohio can find out if his grandma's blood pressure med is linked to 200 other cases of dizziness... but the FDA won't tell him if it's safe? i'm not mad. i'm just... confused. 🤷♀️

just a heads up: if you're using python, don't forget to add time.sleep(1) between requests. i got blocked once and thought my laptop was haunted. turned out i was being a greedy little script kiddie. also, the github examples are gold. saved me 3 days of crying into my keyboard.

Interesting. This feels like the digital version of the old Indian proverb: 'The map is not the territory.' We have data, yes. But data without context is just noise. Who reported it? Under what conditions? Was the patient on five other drugs? The API gives us the 'what' but not the 'why'. Still, better than nothing.

I am absolutely thrilled by this initiative. The transparency, the accessibility, the sheer audacity of making government data usable by the public-this is the future we should all be fighting for. Bravo, FDA. You did good.

You call this 'easy'? Try finding reports for a drug with a hyphen in the name. I spent 2 hours debugging my URL encoding only to realize the FDA's own example code breaks if you use 'metformin-hcl'. This isn't a tool-it's a trap for the naive.

I just want to say: thank you for writing this. As someone who's been trying to help my sister understand her antidepressant side effects, this is the first time I've felt like I can actually dig into something real-not just marketing fluff or scary Reddit threads. You've given me a way to be informed, not afraid. 🙏

The assertion that 'no PhD is required' is not merely inaccurate-it is intellectually irresponsible. Without a foundational understanding of epidemiological bias, confounding variables, and signal detection theory, users are not 'exploring data'-they are performing statistical malpractice. This API should come with a mandatory 12-hour lecture on Bayesian inference before access is granted.

I tried this last week. Found a spike in 'anxiety' reports for a sleep aid I'm on. Posted it on my local FB group. Two people said they felt the same. Then I checked the FDA's own page and saw it was already flagged. Turns out I'm not crazy. Just... statistically significant. 🤓