Pulmonary TB Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps healthcare workers and community members identify households at high risk for pulmonary tuberculosis based on key socioeconomic indicators. Enter the following information to calculate the risk level:

Risk Assessment Result

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the top infectious killers, yet its spread isn’t just a matter of germs. The way people live, earn, and access care can lift or trap whole communities in a TB cycle. This article unpacks the key socioeconomic drivers behind pulmonary TB, shows how they interact, and offers practical steps for policymakers, clinicians, and community leaders to cut the disease at its roots.

Key Takeaways

- Extreme poverty and crowded housing are the strongest predictors of TB infection and disease progression.

- Malnutrition, HIV, diabetes, and smoking amplify risk by weakening immunity.

- Migration, rapid urbanization, and limited health‑care access create hotspots in slums and refugee camps.

- Targeted interventions-cash transfers, nutrition programs, and community‑based DOTS-cut transmission more than drug treatment alone.

- A simple risk‑assessment checklist can help health workers identify high‑risk households for early screening.

What Is Pulmonary Tuberculosis?

Pulmonary Tuberculosis is a contagious respiratory disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It primarily attacks the lungs, producing cough, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 10million people fell ill with TB in 2023, and almost 1.5million died-over 95% of deaths occurring in low‑ and middle‑income countries.

Poverty: The Core Driver

When household income falls below the international poverty line (US$1.90 per day), several risk pathways open simultaneously. First, poor families often live in substandard housing with inadequate ventilation, fostering airborne transmission. Second, limited finances mean delayed health‑seeking, resulting in prolonged infectious periods.

Data from the Global TB Report 2024 show that the TB incidence in the lowest income quintile is more than three times that of the highest quintile. In India’s Uttar Pradesh state, districts where over 60% of households live below the poverty line report TB rates exceeding 300 per 100000 people, compared with under 80 per 100000 in wealthier districts.

Overcrowding and Housing Quality

Overcrowding-typically defined as more than two persons per bedroom-creates the perfect environment for Mycobacterium tuberculosis droplets to linger. Studies in Brazilian favelas found that each additional person per room increased the odds of a TB infection by 22%.

Beyond sheer numbers, housing quality matters. Leaky roofs, damp walls, and lack of windows reduce air exchange, raising the concentration of infectious aerosols. WHO’s “Housing and Health” guidance recommends a minimum of 10m³ of living space per adult to keep indoor pathogen levels low.

Nutrition, Immunity, and TB Susceptibility

Malnutrition weakens the immune system, making latent TB more likely to become active. A meta‑analysis of 18 cohort studies found that a body‑mass index (BMI) below 18.5 doubled the risk of progressing to active pulmonary TB.

Micronutrient deficiencies-especially vitamin D, iron, and zinc-also impair macrophage function. In South Africa’s Eastern Cape, a community nutrition program that provided weekly food parcels reduced new TB cases by 15% over two years.

Co‑morbidities Linked to Socioeconomic Disadvantage

Several health conditions that are more prevalent in low‑resource settings act as TB accelerators:

- HIV infection compromises CD4+ cells; people living with HIV are 20-30 times more likely to develop active TB.

- Diabetes raises TB risk by about threefold and hampers treatment success.

- Smoking damages lung tissue, and smokers have a 2-3 times higher risk of TB infection and mortality.

These co‑morbidities cluster in impoverished groups because of limited preventive care, poor diet, and higher exposure to tobacco smoke.

Migration, Urbanization, and Mobility

Rapid urban growth pushes millions into informal settlements where the factors described above converge. In Kenya’s Nairobi slums, TB prevalence is nine times that of the national average.

Migration adds a temporal dimension: mobile populations often miss routine screening and may delay treatment while moving between regions. Refugee camps in South‑Sudan have reported TB attack rates of 450 per 100000, driven by overcrowding, malnutrition, and disrupted health services.

Access to Healthcare and Health Literacy

Even when health facilities exist, out‑of‑pocket costs, long travel distances, and low health literacy hinder timely diagnosis. A 2022 survey in rural Bangladesh showed that 68% of TB‑symptomatic individuals waited more than three weeks before seeking care.

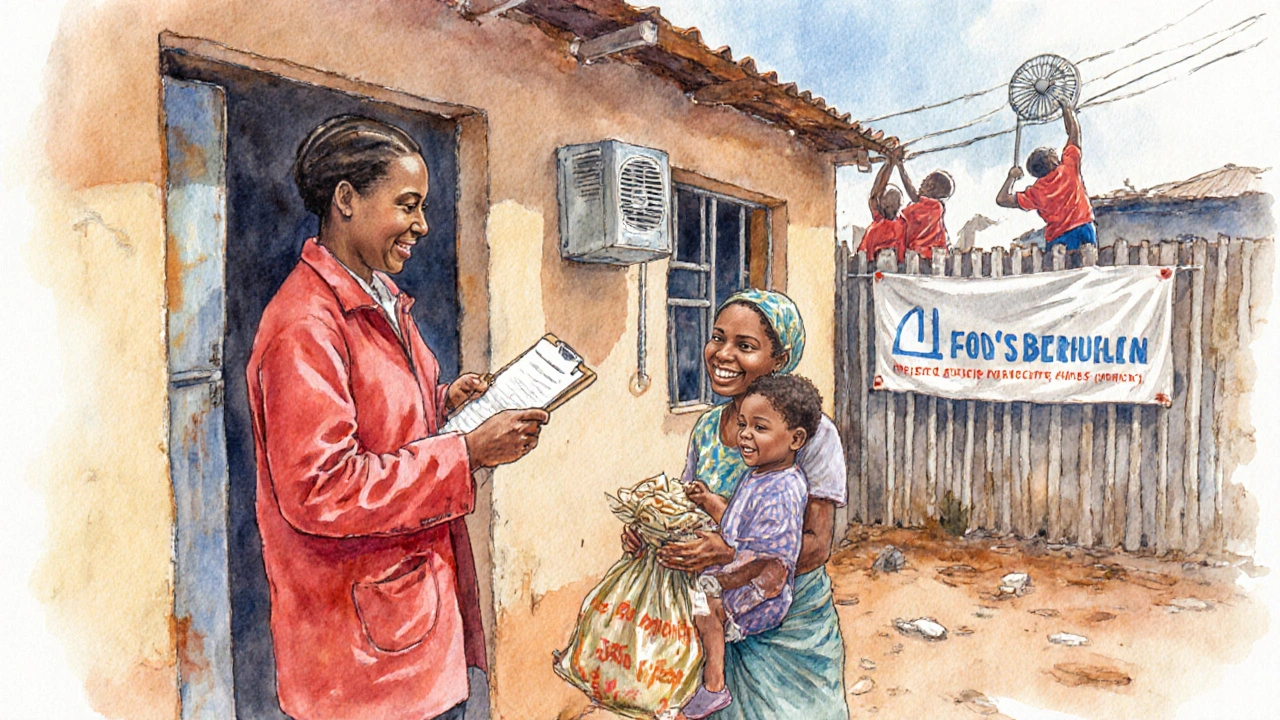

Community health workers (CHWs) can bridge this gap. The Directly Observed Treatment, Short‑course (DOTS) program, when combined with CHW‑led door‑to‑door screening, lowered default rates from 15% to 5% in Peru’s Andean region.

Stigma and Social Exclusion

Stigma discourages people from admitting symptoms or adhering to therapy. In many cultures, TB is associated with poverty or immorality, leading to isolation. A qualitative study in Vietnam found that 42% of patients delayed treatment because they feared being ostracized.

Addressing stigma requires community education, involving local leaders, and ensuring confidentiality in testing.

Mitigation Strategies: A Socio‑Economic Lens

Purely biomedical solutions miss the forest for the trees. Integrating socioeconomic interventions yields measurable impact:

- Cash Transfer Programs: Conditional cash assistance for low‑income families improves nutrition and treatment adherence. Mexico’s “Progresa” pilot cut TB incidence by 12% in target villages.

- Housing Improvements: Ventilation upgrades and housing subsidies reduce transmission. In Peru, installing exhaust fans in 1,200 homes lowered community TB rates by 8%.

- Nutrition Support: Food vouchers for TB patients boost cure rates from 78% to 92% (study in Ethiopia).

- Integrated Disease Management: Co‑screening for HIV, diabetes, and TB in primary clinics shortens diagnostic pathways and improves outcomes.

- Community‑Based DOTS: Training local volunteers to observe treatment and provide education cuts default rates dramatically.

Policy makers should prioritize a “social protection + health” bundle rather than funding TB medication alone.

Risk‑Assessment Checklist for Front‑Line Workers

- Is the household income below the national poverty line?

- How many people share a sleeping room? (>2 per room = high risk)

- Does the patient show signs of malnutrition (BMI <18.5)?

- Is there known HIV or diabetes co‑infection?

- Has the individual recently migrated or live in a refugee/IDP camp?

- Can the patient reach a qualified health facility within 2hours?

- Does the patient report stigma or reluctance to seek care?

Positive answers to three or more items should trigger immediate sputum testing, chest X‑ray, and enrollment in a socio‑economic support package.

Future Directions and Research Gaps

While the link between poverty and TB is clear, quantifying the cost‑effectiveness of combined social‑health interventions remains a challenge. Longitudinal studies that follow cohorts across income transitions could reveal whether upward mobility directly reduces TB incidence.

Additionally, digital tools-mobile reminder apps, tele‑consultations, and GIS mapping of hotspots-show promise but need rigorous evaluation in low‑resource settings.

| Risk Factor | Primary Mechanism | Effective Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Poverty | Delayed care, poor nutrition, crowded housing | Cash transfers, free diagnostic services |

| Overcrowding | Increased aerosol exposure | Housing subsidies, ventilation upgrades |

| Malnutrition | Weakened immune response | Food vouchers, supplemental feeding programs |

| HIV/Diabetes | Compromised immunity & higher bacterial load | Integrated screening & co‑treatment pathways |

| Migration/Urban Slums | Rapid spread in poorly serviced areas | Mobile clinics, community‑based DOTS |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does poverty increase the risk of TB?

Poverty limits access to nutritious food, safe housing, and timely medical care. All three factors create an environment where the TB bacteria can thrive and spread.

Can improving ventilation alone reduce TB transmission?

Ventilation cuts the concentration of infectious droplets, but it works best when paired with early case detection, treatment adherence, and reduced crowding.

How does malnutrition affect TB progression?

A weak immune system can’t contain latent TB bacteria, so they multiply and cause active disease. Restoring adequate calories and micronutrients helps the body fight the infection.

What role do cash transfer programs play in TB control?

Conditional cash transfers give families the resources to eat well, travel to clinics, and complete treatment, which directly lowers transmission and mortality.

Are there digital tools that help track socioeconomic TB risk?

Mobile apps can log treatment adherence, send nutrition reminders, and map hotspots using GIS. Pilot projects in India and Kenya show improved case detection, but large‑scale validation is still needed.

The correlation between per‑capita income and TB incidence underscores the need for targeted socioeconomic interventions.

Nice overview, but let’s not pretend the poverty line magically fixes everything – you still need robust public health infrastructure. Without ventilated housing and accessible diagnostics, even the best cash‑transfer schemes will fall short.

Yo, the nutrition link is real – low BMI doubles risk, so food parcels matter. I’ve seen rural clinics where a simple protein supplement cut new cases by 12% in a year. The data’s solid, even if the write‑up’s a bit dense.

What they don’t tell you is that big pharma is using TB as a testing ground for their next profit pivot. The money poured into ‘cash transfers’ is just a distraction while pharma firms line up patents on new (expensive) drug combos. Wake up!

Interesting theory, but the WHO’s 2024 Global TB Report shows a 15% drop in incidence where cash‑transfer programs were paired with community DOTS – not because of any shadowy pharma agenda.

While everyone gushes over housing subsidies, the real driver is microbial virulence evolution in densely packed slums, a factor grossly under‑estimated in policy circles. Ignoring pathogen adaptation means we’re fighting a moving target with static tools.

You raised a good point about pathogen adaptation, but a quick note: it’s “virulence evolution”, not “virulence evolution”. Also, coupling housing upgrades with active case finding is a proven synergy that many programs overlook.

All these angles point to one thing: we need integrated solutions that blend socioeconomic support with strong healthcare delivery. Bridging gaps between NGOs, governments, and communities will make the biggest dent.

Statistical breakdown: in regions where per‑capita income < $1.90, TB prevalence averages 280/100k versus 78/100k in richer zones – a relative risk of 3.6. Housing density adds another multiplicative factor of 1.8 per additional occupant. Co‑morbidities such as HIV raise the odds ratio to 22.0, confirming the synergistic risk matrix. The policy implication is clear: multi‑layered interventions outperform single‑axis approaches.

That analysis is spot‑on, yet let’s not forget that numbers only tell part of the story. First, the human element-community trust-can dramatically sway the success of any intervention. Second, the timing of cash transfers matters; delivering aid during peak harvest can boost nutritional status more than during lean months. Third, we should consider that over‑reliance on indoor ventilation fixes can backfire if households close windows to keep out cold. Fourth, the interplay between HIV treatment adherence and TB prophylaxis is a delicate dance requiring synchronized supply chains. Fifth, data from Peru’s housing upgrade pilot shows an 8% reduction, but that was achieved alongside a massive public awareness campaign. Sixth, any policy that ignores gender dynamics will miss a key transmission vector, especially in matriarchal societies. Seventh, the “one‑size‑fits‑all” approach fails in refugee camps where legal status limits access to formal healthcare. Eighth, scaling up community health workers must be paired with robust training to avoid misinformation. Ninth, we need to measure outcomes not just in incidence but also in quality‑adjusted life years. Tenth, the private sector can play a role, but only under strict price controls. Eleventh, digital tools for risk‑assessment can improve coverage, yet they require reliable electricity. Twelfth, the stigma reduction component can’t be an afterthought; it must be woven into every outreach effort. Thirteenth, policy coherence across ministries-health, housing, finance-is essential for sustainability. Fourteenth, monitoring and evaluation frameworks should be built from day one. Finally, the ultimate goal is to eliminate TB, not just to manage it, and that demands bold, coordinated action.